I generally don’t think it’s legit to count a Best of… or Greatest Hits album amongst one’s favorites. Since they are inherently a compilation of “favorites”, they don’t really count as “albums” in the traditional sense, being a single work, a group of records built and put together in a manner where they fit with one another for that given output. It’s sort of cheating.

Live albums are similar, but occupy an even grayer area, since they could be just particularly great performances and versions of a given song, or more aptly, the energy from the show itself creates a different feel for a given record or even the album as a whole. But the same concept applies.

But for me, one Greatest Hits album in particular at once embodies and circumvents all these constraints, and for several other ancillary reasons sits in my personal Top 5 of all time: The Best of Donald Byrd.

The album is most certainly a collection of his greatest works, but is presented in a manner that doesn’t feel as disjointed as one might imagine a jazz (/funk/soul) album might be, having been cobbled together with works from various albums; jazz albums (of the Blue Note era in particular) having been famous for a single thematic vein running through each work, the songs tethered in at least some way to a shared maypole.

Byrd’s Best of… is not your typical Greatest Hits album, in the same way Byrd himself isn’t anywhere close to your typical artist. For one, his music spans close to four decades in the run-up to this album’s 1992 release. For a jazz artist of his ilk in this era, that amount of time alone means he was party to a broad evolution of the space in which he could and would compose and perform. That breadth is not reflected in the track listing itself per se, the selections for The Best of… having come from five albums (Black Byrd, Street Lady, Steppin’ Into Tomorrow, Places and Spaces, and Caricatures) which were all released between 1972 and 1976, but the breadth of his oeuvre and his myriad influences are certainly reflected in the album’s overall musical arc.

And the protagonistic wails of Byrd’s signature trumpet, coupled with the warm, somewhat haunting orchestral elements of his accompanying band and exquisitely of-the-moment soul vocals, end up tying together the songs in a way that feels far more intimate and intentional than most other similar works. It also includes a single live track, a particularly funky and driving version of one of his best records “(Falling Like) Dominoes”, which looks like it would be an odd inclusion. But it just fits. Perfectly. Unlike most Best of… albums, which feel like compilations with no particular connectivity, this feels like a story.

The album as a whole creates a mood that, for me, feels at once vintage and dusty, compelling and urgent, and different; yet at the same time eminently contemporary, warmly environmental, and comfortingly familiar. It feels special. And preternaturally cool.

And not just for me, it seems, as it is a perennial favorite, as are a Donald Byrd Pandora/Spotify mix, in any number of party settings, or even over dinner. My wife and I entertain quite a bit, and I’m always good putting Donald Byrd on, regardless of the crowd. Like really good weed, Byrd always seems to lend the right uplifting, pleasantly introspective mood to the proceedings. His music is unexpectedly weighty, but eminently fun.

As a result, Byrd’s sound has a sort of cosmic appeal to it. Upon reflection, that is likely due to it being a defining “sound” of the years leading up to and immediately after my generation’s time in utero. Like the smell from the grill for some, his music seems to spark up nostalgia for many in my age realm, given its place as the kind of welcoming, catch-all background funk soundtrack for many of our childhood memories. For me, it actually takes me back to several different times of my life simultaneously on its own, living elegantly beyond its years in a manner that only the best, tastiest horn and drum loops, in the hands of the hip-hop’s most unique and talented producers, could do, via the hip-hop of my adolescence. Perhaps more than any other music, Donald Byrd’s speaks to all of me.

Oddly enough, I came into it via hip-hop, in a manner that has long been a fruitful route for me in terms of finding new favorites: the liner notes of other albums. Having grown up a hip-hop head of the most committed order, with a rather voracious appetite for any information I could glean about the music and the culture at large itself, I always took a special sort of nerd’s pleasure in digging into the sample credits of a given album. Having realized early on, thanks at first to “Walk This Way”, several instrumentals on Licensed to Ill, He’s the DJ, I’m the Rapper, and most notably Strictly Business, I was well aware that my favorite music was structurally a pastiche of other artists’ works, chopped and flipped and rolled out in a new and often more exciting way for a younger audience to enjoy.

And while I certainly did enjoy the fruits of that process, I remember one particular lyric from Stetsasonic’s Daddy-O on “Talkin’ All that Jazz” which caught my attention, and led me down the path of exploring the musical ingredients that made hip-hop the soulful, moving, multi-layer feast to which I so gluttonously took:

Tell the truth: James Brown was old ’til Eric & Ra came out with ‘I Got Soul’.

I knew hip-hop producers took bits of existing instrumental tracks to form the basis of new beats. I couldn’t yet identify the signature snare from “Funky Drummer”, but I certainly recognized how frequently I seemed to hear it being out to use in hip-hop. But the more obvious presence of “I Shot the Sherriff” on “Strictly Business” or the theme from “I Dream of Genie” on “Girls Ain’t Nothing But Trouble” or “When the Levee Breaks” on “Rhymin’ & Stealin’” was clear enough for anyone to understand what was happening.

This approach eventually became so dumbed down, so naked and simplified that it was later lambasted and lampooned by 3rd Bass on “Pop Goes the Weasel” (“Why not take a Top 10 pop hit, vic the music and make senseless rhymes fit?…”) – ironic, I might add, in retrospect, given that the use of Peter Gabriel’s “Sledgehammer” on that very track was one of the group’s most blatantly singular, least nuanced examples of what is otherwise brilliant, multi-layered sampling in their catalog, in my opinion. Which is to say nothing of Puffy’s eventual murdering of the idea of subtlety in sampling altogether, but I digress.

But until that point I hadn’t really grasped the subtlety with which this was occurring with less recognizable, more micro-level samples and snippets – in particular from the Funk, Soul, and, ultimately Jazz worlds. Horn loops, snare grabs, basslines, an occasional flute or recorder – the individual instrumentation involved in the construction of well-made hip-hop records became a rabbit hole down which I would gleefully frequently plummet.

Of course there were limitations. Public Enemy records were of course notoriously dense in terms of samples. To the point where I ceased even bothering to try to pull apart the symphony ringing out of my Walkman for its component parts, choosing instead to just sink into the mayhem. Same goes for Paul’s Boutique, a record that I admittedly didn’t “get” when it was released, given its intentionally weird, busy sonic composition, and dusted out content, which I only was able to successfully dig into a half decade after its release. Trying to note the individual samples, skits/interludes and all, on that record was an exercise in futility. So much so that when KEXP famously executed its utterly brilliant Sample Series programming – playing the entire track of each and every individual record that was sampled in the making of seminal hip-hop albums back to back (can’t describe how much I love this idea AND its execution) – a few years back, it had to devote a more than 12 hour window to Paul’s Boutique.

But there were also surprising finds amidst what was a very James Brown, George Clinton/Parliament, and The Meters-heavy catalog. One such gem was the afore-mentioned Donald Byrd. Shortly after this time, coming out of the increasingly energized, aggressive tempos and soundscapes that fed the rise of gangsta rap and its East Coast analogs, and perhaps subsequent to the large scale pressure release that was the LA Riots, hip-hop as a whole began embracing a more mellow tone, and bringing jazz samples to the fore.

Producers like DJ Premier and Pete Rock, among others, ingeniously incorporated mellow jazz samples into otherwise quintessential East Coast boom-bap, creating a near incongruous yet somehow perfectly balanced sound that was the foundation for what is considered by many to be the final stretch, the culmination, of the Golden Era. Around this time, Preemo’s Gang Starr partner Guru dropped the aforementioned legendary side project Jazzmatazz, and its signature track “Loungin’”, vaulted an artist who had in many ways played second fiddle to his era’s most legendary names (having played alongside Cannonball Adderley, Coltrane, Monk, and others at Newport and elsewhere), into the long-overdue spotlight. Hip-hop bonafides having now been solidified, I set out to purchase a sampling of his works, assuming an artist of his stature and renown (and longevity) would certainly have a Greatest Hits or two from which to choose.

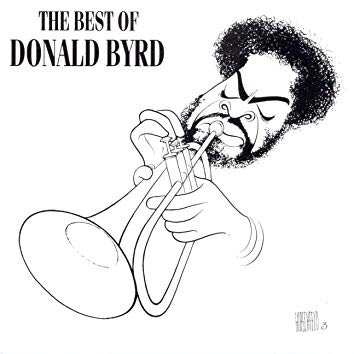

And with one glance at the album art – a classic pen and ink Hirschfeld rendering of Byrd blowing gracefully on his horn, eyes mellowed shut, cartoon fingers dynamically akimbo – I knew the connection was cosmic.

SIDEBAR: For as long as I can remember I had loved Hirschfeld’s drawings, in particular this series of simple caricatures of entertainers of that era. Something about the paradox of starkness and richness of them: simple back and white, forms floating in the blankness of the page, yet swimming with graceful detail and expression in their hair, eyes, ears, and clothing. Perhaps it was the cartoony visages and slightly exaggerated features of recognizable figures cast in these drawings that made them seem more intimate and accessible. Maybe it was Hirschfeld’s ability to capture emotion and character in its simplest ink-on-paper form, or perhaps just the unique brilliance of his talents, but I knew when I saw that album cover that I felt even more connected. Donald Byrd was indeed for me.

That personal, almost spiritual connection would go on to deepen again through hip-hop over the subsequent months and years, in particular through the emergence of one of my favorite producers and beatmakers of all time, Evil Dee. In the fall of ‘93, with my driver’s license on the near term horizon, in the waning days of the Walkman phase of my musical life, Black Moon dropped their seminal New York City hip-hop classic Enta Da Stage.

Featuring rich, multi-layered yet somewhat stripped down beats from the Beatminerz, this album is one of a handful that in my humble opinion perfectly captures the ethos of that era in terms of both the music and the culture. Set to that pace and syncopation that defines (for the most part) East Coast/Walkman hip-hop – built to listen to privately, with a cadence that matches the strident pace of foot travel, beats often mimicking the driving clang and dynamic melody of a ride on mass transit – as opposed to the more lumbering, drawn out melodiousness of West Coast/Car hip-hop, which is built to be listened to in group settings, rolling along in an automobile, funk foundations lumbering along, windows down as the sound pounds, this album, like later iconic NY releases 36 Chambers and Illmatic, sounded at once comfortingly familiar and fresh AF.

And to my somewhat surprise, given the more hardcore nature of Black Moon’s lyrical content and overall approach, at least as compared to the more unifying jazzy appeal of Guru’s syrupy monotone, Byrd’s samples feature heavily. But as is the calling card of truly talented beatmakers, even outwardly incongruous source material meshes seamlessly into the final product right from jump. To wit, my favorite song on a truly front-to-backer of a debut album, “Buck Em Down” is built around an interpolation (and a particularly juiced up, heavily muddied original bassline) of the introductory bars from Byrd’s “Wind Parade”, a song whose soaring, wind chime and strings-driven instrumental tells a much more lush and compelling story than its limited lyrical complexity might otherwise allow.

The fact such a melodic, frankly pretty, song can serve as the foundation for this aggressive, grimy, somewhat haunting homage to Black Moon’s native Bucktown, Brooklyn environs is a testament both to Byrd’s unique musicality and to the Beatminerz’s wizardry. All the more impressive when juxtaposed against the more heavy-handed sampling of the subsequent era, where producers like Puff simply lifted an original track whole, instrumental, hook and all, and re-Eq’d it to grand pop success (and a grand “Nahh…” to the defining ethos of hip-hop as a whole up to that point), which is part of what makes me love Black Moon, and by extension Donald Byrd, even more: the genius of subtlety, the brilliance of originality.

There is a special connection for me to both of these works. So much so that a pen-and-ink drawing of the famous Enta Da Stage album cover by renowned graffiti/graphic artist Rhek graced my daughter’s nursery for the first 8 months of her life (until she began continually pulling it off the wall during diaper changes and I had to move it to the living room).

It is partly due to this connection that I always bristle when I hear people go on about how much they love hip-hop, as somehow proven by the fact that they ONLY listen to hip-hop. Since 95% of hip-hop is a derivative, albeit incredibly creative at its best (admittedly unlistenable at its worst, but that’s another topic for another time), art form, the appreciation one can have for a DJ Premier or Pete Rock track, or Black Thought lyric, etc. can only extend so far if one isn’t grounded in those artists’ influences, in their original source material. Not unlike “sneakerheads” of today, who have no knowledge of, nor any interest or even intellectual curiosity in, anything that dropped prior to 2008 (much less the shoe game before it actually became a thing in the early 2000s), if that’s you, then you’re missing the point. On some level, if you truly want to be down, you have to do the knowledge. You can run out and cop the LeBron 16 Medicine Balls, or the Air Trainer 3s that informed their design, but if you don’t recognize the import of the original Air Trainer 3s, and understand the retro’s provenance, then you’re a poser. Period.

Recognizing that now unmistakable snippet of Byrd in the “Buck Em Down” beat, as incongruous as it was, unearthing that nugget of precious information that ties a favorite modern track back to its original, rather obscure source material, is in many ways reverse engineering hip-hop itself – unlockling the puzzle – has always energized my souls . Which is part of what I love about both art forms.

It also remains a technique deftly applied by my most favorite live DJs; few things give me more joy than hearing ?uestlove or Stretch Armstrong or Cosmo Baker or Edan mixing into an instrumental loop many recognize from its sampled modern iteration, only to break into the original funk/soul/jazz/R&B joint by the original artist. The more obscure the better. It always feels like a nod to the purists in the room, to those who, ultimately, love hip-hop as much for what goes into it as for what comes out of it. A musical dap to those who do the work. To those who know. And it always got me like “Yup.”

Or as Guru so aptly put it: “Donald Byrd. Word.”